Language entropy

The other day I found myself (re)learning about information entropy, a subject that fascinated me during university days. Here’s a brief summary.

Information entropy (also known as “average information content”) basically gives us a way of measuring the amount of useful information packed inside some piece of data. But let’s back up.

In physics, the entropy is a measure of uncertainty. The more uncertain some outcome is, the higher the entropy. For example, the smallest unit of information is one bit, which takes on one of the two possible values, 0 and 1. Now, which bit is more useful, one whose value is equally likely to be 0 and 1 (e.g. a coin toss), or one where there is a much higher probability of one value over the other (e.g. “did you win the lottery”)? The 50-50 case packs more information and therefore has a higher entropy (actually, the highest possible for a single bit).

This is Shannon’s equation for entropy:

\[E(X) = \sum_{x \in X} p(x) \log p(x)\]where X is the collection (e.g. a language), x is the single item (e.g. a letter), p(x)

is the probability of the occurrence of x within X, and log is the base two logarithm (we

could use any other base, but this gives us the unit of bits, or “shannons”).

We can loosely translate this equation into the following algorithm for calculating the entropy of some piece of text:

1. Loop through all characters in the text:

- Maintain the counter of occurrences for each letter, representing its frequency

2. Calculate the probability of each letter (frequency / total number of letters)

3. Loop through all letter probabilities:

- Multiply each probability with its negative base-2 logarithm

4. Sum the values from previous step

This is the entropy of the input text. We could attempt approximate the entropy for the whole language by using lots of huge text samples, but it would not be precise, because a language is much more than just a collection of letters grouped into words and sentences. Shannon’s original paper was actually using n-grams, which doesn’t come without its own set of limitations.

I was wondering: How does entropy of a language change if we destroy the fabric of grammar and language rules, and we simply arrange all the words in the sorted order? Turns out, this kind of normalisation results in approximately the same value across all languages (source).

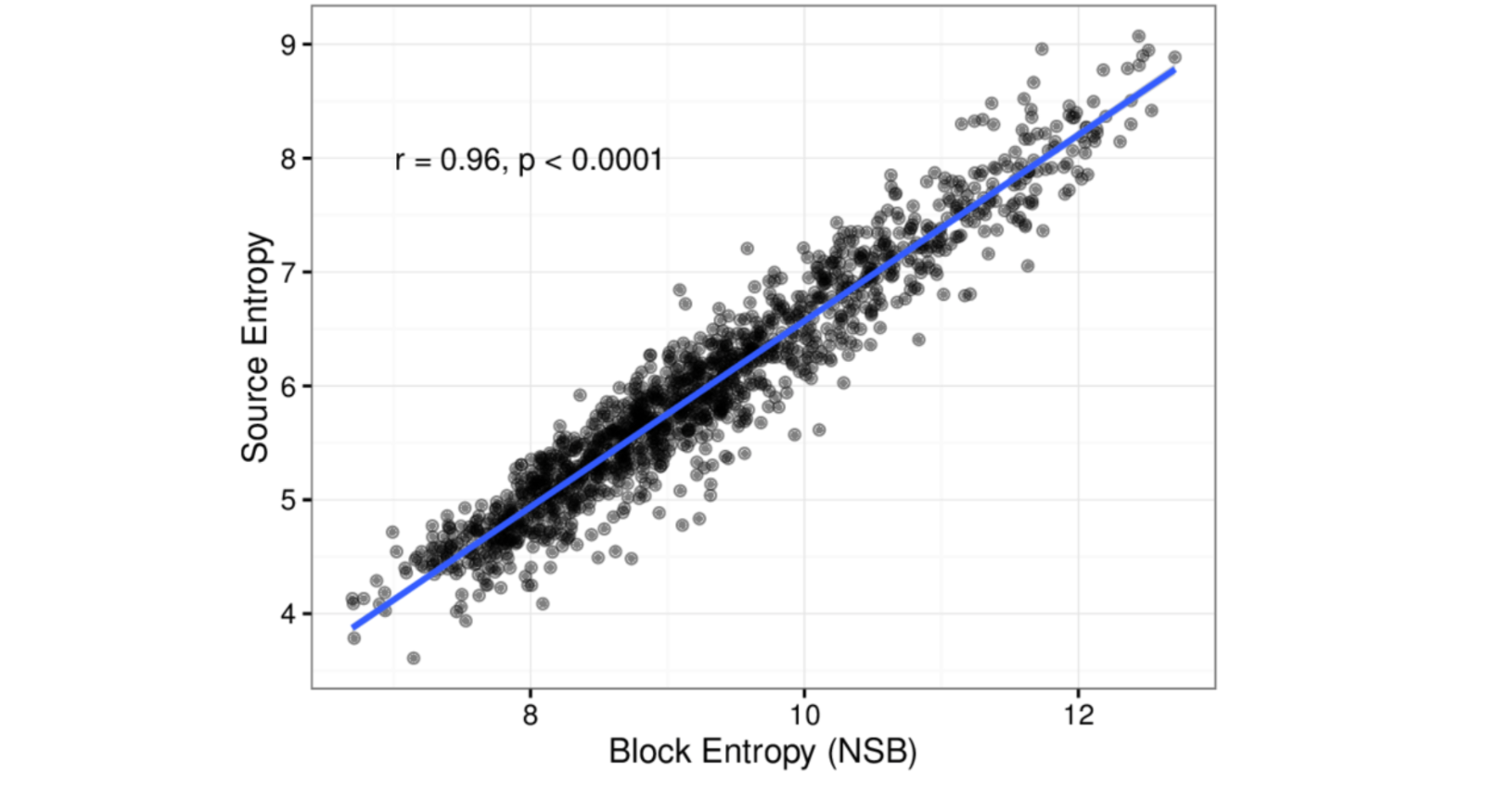

Here’s another question: How quickly does entropy of a language converge to a stable value? Answer: after an average of about 35k when using isolated-words aka “source” entropy, and 38k for n-grams aka “block” entropy (source).

Unsurprisingly, their correlation is linear (page 14):

What about speech?

It has been shown that speech entropy runs at about ~39 bits/sec across all languages (source). This would indicate that, regardless of the grammar, dictionary size or other parameters, we all eventually converge to conveying the same amount of information per second in spoken conversations.

Before I wrap up, a quick note on cryptography: since entropy is a measure of disorder, we can use text entropy to measure the quality of an encryption algorithm (the more disorder, the harder it is to connect it to the original plaintext). And here’s something cool: in an attempt to introduce as much chaos as possible into its pseudo-random process of key generation, popular cryptography tool GNU Privacy Guard (PGP) uses your keyboard and mouse input as a source of entropy. If you don’t move them sufficiently during the key generation process (more specifically, generation of a prime number to be used for asymmetric encryption), you might see a message like this one:

Not enough random bytes available. Please do some other work to give the OS a chance to collect more entropy! (Need 250 more bytes)

But as long as you’re using it yourself (and not e.g. via a script), you should be fine. After all, who’s better at creating chaos than humans?